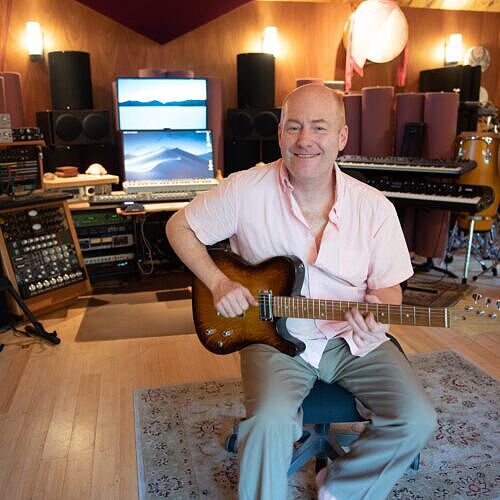

Mac Ritchey, Music Producer

Helping you find the magic in your music since Atari was a thing.

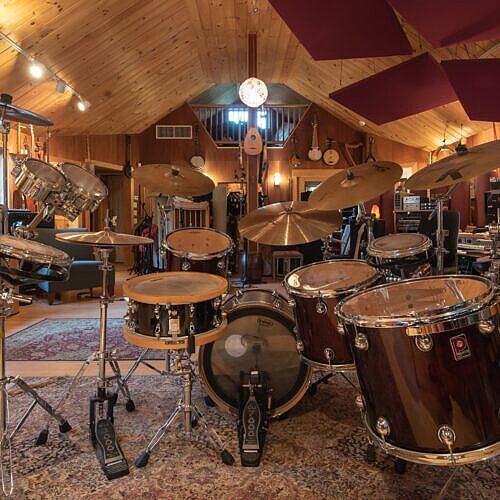

My Place Has the Gear and I Have the Ear

As a producer, I assist artists in getting the most out of their recording process.

Whether it’s diving into the details of an arrangement, coaching a strong vocal performance, or simply providing a relaxed room with an experienced audio engineer, I’m here to help you make your music shine.

Having spent the majority of my life saying things like “let’s do one more pass, and let’s make it sound more purple” and “more chunka chunka on the hmm hmm”, I can safely report that recording music qualifies as my life-long passion.

It is a privilege to be involved in the recording of a song. That song is your song. Let’s do it right.

A Lifelong Passion for Recording

It began with a RadioShack cassette recorder and TV theme songs.

Early audio pirate that I was, I’d hit record just before my song would begin. This is known in the field as a “punch-in” and by 8 years old, I got pretty good at it – before I knew what “running tape OP” meant.

I’ve graduated to ProTools and Nuemanns, but the spirit remains the same: I love recording. More than just the technical aspect of clean tracking and crafty editing, I am most at home when involved in the collaborative capture of The Song. The recording studio is a place where we can dive deep into sound, turning ideas into songs that can make people laugh, cry, fall in love, and generally be the soundtrack for life itself.

But a recording studio, however impressive, is still simply a space. The magic comes from the people who use the space, seeking to capture a song in its best possible form. The studio is also a place for discovery, where microscopic details can be explored that may hold the key to the magic of a production – a shaker track, a key change suggestion, a trusted voice offering a timely “what if?”

This whole thing started for me on a cassette tape.

It’s 1978 and I have a RadioShack cassette recorder. I’m lying on the floor, comfy on the wall-to-wall shag carpet. In front of me is a ludicrously large (and heavy) cathode ray tube built into an attractive, if dated by design, wooden box. It’s not the show that’s about to come on that I’m here for – it’s the theme song.

My first foray into the world of audio recording was capturing my favorite theme songs from television shows. I remember how much joy I experienced successfully capturing those songs, getting the timing just right after the ad but before the downbeat. I recall equally as clearly the feeling in my stomach when I learned how flimsy and fragile the media was, and how quickly and permanently the tape can get damaged or erased. I also learned “the pencil trick” rather young. If you know, you know.

1986 comes along, I’m in my sophomore year at boarding school, and this senior who lives at the end of my hall introduces me to, what I immediately saw as a gift from divine creation, this device called a 4-track recorder. It uses cassette tapes, the very same ones from my TV theme song pirating days, and it allows the user to record four individual tracks.

At different times. Backwards. Change the levels.

Okay, Device which I see as a gift from divine creation: you have my attention.

And so it was in 1986 that I began recording my first album. My dormitory neighbor lent me that four-track recorder for a few weeks, and I was hooked on the process. I recorded basic drum parts with a single cheap microphone in one of the on-campus rehearsal rooms and brought the recorder back to my room to create guitar parts. I didn’t have a bass guitar, but I had my sister’s Roland Juno 106 synthesizer to add some other sounds. Those 7 instrumental songs became my first album, “The Whale’s Greatest Night”, and though it won’t be winning any Grammys anytime… ever… this was a door that had opened for me and welcomed me into a whole new world of creativity.

Shortly thereafter, I acquired my own four-track recorder, still using the fragile and less-than-audiophile-quality media, and by the time I graduated high school, I had recorded seven albums of material, many of which were concept albums inspired by the prog-rock and less main-stream music I was listening to at the time. This set me up for the perfect meeting with another upperclassman once I arrived at Oberlin college for my first semester.

Within weeks of arriving, I was introduced to a senior who had just completed a summer internship at Capital Records recording studio in Hollywood, CA. He introduced me to the concept of preamps, compression, a better understanding of EQ, and this thing we were using back then called Dolby noise reduction. He had an EIGHT TRACK reel-to-reel recorder – the fruit tree was growing bigger fruit. I pulled on my harvesting pants and soon upgraded to eight tracks myself, but I still stayed with the cassette format. Yes, there was a time in history when we had the hubris to try and squeeze eight tracks of audio onto .15” of iron oxide. (Professional media had nearly five times the space per track on which to record.)

Nonetheless, it’s not about the tools, it’s about what you make with them, and I was making anything I could. I started recording demos for other musicians, creating drum parts on my trusty Roland R-5 drum machine (I still miss that workhorse), and backing them up on whatever extra instruments they wanted in their arrangement that I could play for them. This marked the moment that I began working with “clients”, learning how to coach compelling vocal performances, looking for just the right voicing inversion on a chord, adding a synth pad to glue things together in the background. For about 6 years, I put thousands upon thousands of hours on that 8-track recorder and it served me very well. I can still hear the “analog quality” in those early recordings, even on a medium as limited as a cassette tape. But we all know where this story goes.

Enter: the digital age.

Most, if not all, professional audio engineers who were ascending in the ranks graduated from cassette (if they ever even bothered) to reel-to-reel of some sort, sporting either 8, 16, or if you had “the big gig”, 24 tracks. This was all still on iron oxide and in the universe of analog recording – if you wanted to do an edit, you literally reached for a razor blade and cut and spliced the tape itself. This young audio engineer, however, was coming of audio-age just as the digital revolution was barreling towards us like a freight train. Typical of my generation, choosing features over fidelity, I hungrily gobbled to up two Alesis ADATS as soon as I could get my hands on them. These were digital audio recorders that utilized VHS tapes as their media. This was one of the most unreliable, finicky, prone-to-disasters choices for media you could imagine, but as long as the humidity didn’t change too quickly and the audio gods favored you on that particular day, you could potentially get through a day of work without some form of disaster befalling you and your session. Potentially. Unlikely though.

Let’s also not forget their sound. ADAT audio was awful like scraping a razor blade on glass, but it was a digital medium, meaning you could bounce tracks without losing fidelity. You could program exactly when and where the machine would start recording on a track during overdubs. These were all huge advancements in the world of recording, and although I was working on a medium that would have ten years of tempered glory, tops, this was the big first decade of my truly professional development. My shingle was hung: I had clients (bands, singer/songwriters, even a few jingle sessions and a guided meditation or two), and I was well on my way to my 10,000 hours by the time I hit 25.

It was around this time I released my first CD, “The Sagebrush Letters”, taking my tracks to a far more professionally outfitted studio than my mother’s basement and mixing the album there under the leadership of an experienced mix engineer. Some of those days were 12 to 14-hour work days, and I would occasionally sleep on the couch by the light of Lexicon reverbs and Eventide harmonizers purring gently in the racks, knowing we would wake them up again in a mere matter of hours for another day of work. Why go home when the fun was right here?

By the end of the 20th century, a company called Digidesign was improving upon an earlier software platform they had developed called “Sound Designer II”, a two-channel digital audio editing program that could run on an early Macintosh computer with specialized hardware called a NuBus card. It was finicky, prone to crashing, and had limited application to me in 1990. I used it a few times simply because that was the class assignment – create a piece of music in Sound Designer II – but at that time I still preferred working on my 8 track cassette.

Between 1989 and 1999, those clever UC Berkley graduates at Digidesign had fed the software a steady diet of spinach of awesomesauce, turning a simple two-track editor into a full-blown computer-based multi-channel recording system, capable of doing things we could barely even dream of doing back in the day. Copy, paste, chop, edit, move, reverse, time up, pitch correct, speed up, slow down, split stereo into dual mono, invert/phase flip – all with the click of a mouse.

We called it ProTools. It was paradise found.

Except of course that one had to reboot their computer every hour or two when a tiny change inexplicably caused the computer to crash, and you had to be very careful which extensions were loaded on your machine, and you had to set your computer never to go to sleep. What? It’s true.

But the next twenty years of that story has already been written, and we know it well. ProTools is now a household name, remarkably stable, and those early magic tricks we marveled at in 2000 are now comically simple compared to what we are capable of now. There are numerous digital audio recording software platforms available, some of them free to anyone with an iPad and some curiosity. The tools have become so powerful that many songs created these days are more a function of the technology used than the artistic inspiration that started the process. I am undoubtedly a ProTools devotee, and having worked on the platform for 24 years rarely do I have any need to look elsewhere. The new era of recording has arrived, and with it the trappings of technology guiding the art rather the other way around. (nice) As someone who focuses primarily on recording acoustic instruments and live performances, rather than primarily electronic music, this risk is slightly reduced for me, but I still keep my eyes on the prize and sterile music gets shown the door.

We don’t need huge facilities with trained staff and hundreds of thousands of dollars of gear to record, and although better gear means a better signal path, it does not promise a better musical performance. A moving musical presentation, a single take played live, captured by the lowliest of microphones will always overshadow a weak performance recorded with the most expensive gear and edited to within an inch of its life. The tools are the technology that help us create art in the modern era, and if we keep the target in focus (capturing the most compelling performances of music we can), these new tools allow us to record anywhere at just about any time. Musicians can now work in living rooms, in borrowed spaces, in RV’s driving down the road, outside in the street. Wherever a musician feels an inspired performance coming on, we can capture it in high fidelity with increasingly portable, powerful, and affordable gear.

But what makes for a compelling musical performance? Humanity. And the gear will never give us that.

I’ve spent the majority of my life recording audio, creating albums, building songs out of silence with others, through constant collaboration, sharing of ideas, listening, reflecting, growing and improving my craft. And it is in the working with others that we find some of the most vibrant musical magic, music that we never expected to come into being until we started digging into that 4-note melody or that 2-bar riff to see where they may go, spurred on by imagination and the joy of creation.

My recording skills have significantly evolved from days of the humble .15” cassette tape, but I will never forget its place in my life. A little curiosity – and knowing the pencil trick – can get you a long way.

CloseRecording Resumé

Evren Ozan

Images Of Winter

As Things Could Be

Dhara

Alluvia

Yarina

Yawar Wawki

Various singles

Dreadnaught

Northern Burner

Sarah Fimm

Cocooned

A Perfect Dream

TaranataCeltica

Live In Italy

Bob Lord

The Six Observables

Raúl Molina

Transito

Curi Cachimuel

Llaktapura

Esthema

Long Goodbye

IV

35th Parallel

The Green Vine

Crossing Painted Islands

Evolutia

Walk Like A Cow

Plays The Traditional Music Of Walk Like A Cow

The Response

The Response

David Maxwell

Blues In Other Colors

Four Flute Flight

Touch The Sky

David Ward

Destiny Takes Her Time

Eric Colville

Afraid To Dance

Five

X-Ray Glasses

Motokops 2000

…Only Pieces Remain

The Torment Of Existence

Pam McCann

Kinder Enemies

Back On The Train

Instantly Stronger

Less Talk More Play

Fadi Jano

Halet Tarab

George Lernis

Widening Our Circle

Swarm Of Eyes

Telergy

Lloyd Thayer

Jerome Deupree

Floyds Row

Kelly Buchanan

Bastard Daughter

Marcus Gale

So Glad

Lindsay Smith

Tales From The Fruit Bat Vat

Hazel Blue

[eponymous]

Wishful Infinitives

The Sagebrush Letters

202 The Band

En Route

Robert McClung

Dust Covered Man

Resinate

Sonic Assembly

Uniting Ageless Minds

Eleventh Hour Magic

Mac Ritchey

Amphora

A Little Bit Of A Long Short Trip

Randy Armstrong

No Regrets

Orange Tree Samples

Passion Flute VST

A Thousand Years (film sountrack)

Voices On Antisemitism (podcast)

Annie Finch

Calenders

Sonam Rose

Healing Beyond Cancer

Spirit Passages

Shamanic Drumming

Becoming The New Human

And many, many others…

Close